Miso

Developed in Japan over a millennium ago, MISO is a full-bodied savory or sweetly salty fermented food which adds deep flavor notes to both traditional Japanese and Western dishes, alike, yet also has health-promoting properties and essential antioxidants to maintain good health in our modern world.

Secrets of Japanese miso

Why Japanese live long

According to the World Health Organization (2015), Japan has the longest overall life expectancy of any country in the world at an average of 83.7 years. The reason for this phenomenon? Common knowledge tells us that lifestyle (i.e. exercise) and diet are the biggest contributing factors for increased life expectancy. In Japan, walking, bicycling, and working in the garden are regarded as desirable activities for all ages, while a fermented foods– and seasonal fruit- and vegetable-based diet is held to be the ideal. Western and modern foods have eroded this traditional diet to a degree, but older Japanese still adhere to the time-honored food customs of the last half a century. Veering too far off this course could have drastic health consequences, so Japan should honor and encourage a diet rich in the traditional foods that have contributed to making Japan #1 in life expectancy.

Fermented foods are well known for encouraging good bacteria to flourish in our bodies and thus promote good health. Miso, especially in its unpasteurized state, is the perfect vehicle to introduce these magical properties into our diet and can be added in moderate amounts to almost any dish which uses salt: even Western cakes and cookies!

Miso is a crucial seasoning agent in low-salt as well as low-fat cookery as, even in small amounts, miso punches up the flavor in foods. Shojin ryori, the gentle, seasonal cuisine of the Zen Buddhist temples, relies on miso in any number of ways to infuse dishes with depth and to tease out the natural umami of different ingredients. Miso is the unifying and essential ingredient in these cuisines, along with protein-rich sesame. Without miso, shojin ryori would venture into the realm of bland, but with miso, becomes sublime.

Japanese miso has been credited with numerous extraordinary powers: the ability to ward of cancer, combat radiation sickness, and even negate smoke inhalation or exposure to pollution. Whether or not these claims are exaggerated, there is clear and irrefutable evidence that a bowl of miso soup a day will impart beneficial health properties that will lead to long-lasting lower blood pressure and overall increased intestinal well-being. One soup, one side dish (plus rice) make up the Buddhist ideal of a complete meal (ichiju issai) and it is impossible to deny the roots of this historic food enjoyed for hundreds of years in the heart of Japan.

Why Japanese Miso is so healthy

Due to the interaction between soybeans and koji-inoculated grains that, along with salt, are the basic ingredients used in the preparation of miso, miso has a number of essential health-giving components. Miso suppresses high blood pressure: By drinking miso soup regularly, one can reduce overall sodium intake by 30%. Furthermore, miso directly lowers blood pressure due to inherent components that make it easier to release salt from the kidneys. Ingestion of one bowl of miso soup a day also improves blood vessel age and has skin-beautifying and moisturizing effects because of the antioxidants contained in miso. There is also strong evidence which points to consuming miso in the daily diet as a way to ward the body against cancer. While all lofty claims, the overwhelming evidence does seem compelling, and the fact that the people of Japan live longer than in any country in the world is proof that Japan historically has had a healthy lifestyle and diet.

History & Culture of Japanese Miso

History of Miso

The earliest record of the use of miso in Japan appears in the Taiho code of 701. Scholars cannot say with absolute certainty whether miso was first introduced to Japan from Korea or China or whether it evolved organically from within Japan itself, or indeed all three. While various theories exist, it is commonly held that the method of making miso from tama (fermented miso balls) originated in Korea and is the progenitor to most Japanese farmhouse miso. Whereas the method of fermenting miso from koji-inoculated grains was transmitted from China, most likely through Buddhist channels, and was the method avored by the nobility and in monastaries. Furthermore, there is speculation that the evidence of salt-making during the prehistoric Jomon period and the fermented _sh and meat oncoctions of Yayoi (300 B.C.–300 A.D.) point to a native miso-making culture, which naturally evolved in the northeastern region of Japan, known as the “miso heartland.” In any case, the making of miso can be traced back undisputably to as early as 700 A.D. — well over 1000 years ago.

Miso was mentioned in the Engishiki (927 A.D.) as a soup ingredient for the wealthy in the 10th century, but because of its expense, most people could only eat a small dab of miso on rice or pickled vegetables. Also miso was an important seasoning added to simmered fish or vegetables, and thinned with vinegar, became a sauce for a salad of raw fish (namasu). By the 18th century, soy sauce had virtually replaced miso as the flavoring agent in urban areas, and by the year 2000, 90% of miso used in Japan was used for soup.

Miso soup, as we know it today, evolved in the Muromachi period (1336–1573) when miso soup–making parties emerged as a popular past time. The host would prepare the basic soup (atsumejiru) with seasonal ingredients and the guests would bring side dishes to enjoy with the communal soup. A rudimentary version of instant miso soup developed in Muromachi by samurai going to battle. Dried taro stems were simmered in miso then braided into long ropes (imogara nawa), which the samurai wore around their waists. The samurai cut pieces of the miso-simmered rope off while on the battlefield and poured boiling water over to create an instant life-sustaining ration.

The main flavoring of Japan shifted from miso to soy sauce in urban areas over a period of more than two centuries. However, in rural areas, miso remained the seasoning of choice over soy sauce well up to the end of the 20th century. And while many farm families continued making their own miso up until the 1950s, it was rare to make soy sauce because of its difficulty. Nonetheless, miso adds saltiness, flavor, and fragrance to food, so is experiencing a worldwide increase in popularity and use. And with a high content of glutamate acid, miso contributes both tart and sweet elements along with complex flavor structures. The paradox of Japanese haute cuisine is the saying: “Not to cook is the ideal of cooking,” and miso is an exceptional method to introduce complex, fermented salt notes to any cuisine.

Miso in Art & Culture

The miso soup we consume today has been a fixture in the daily life of Japanese since it was popularized and became mainstream during the Muromachi Period (1336–1573). Images of making miso appear in historical drawings throughout the ages and even the colorful ukiyo-e paintings of Japanese cultural life depict people sipping bowls of miso soup and mothers feeding their child miso soup. Miso soup parties developed popularity in the Muromachi Period, and thus firmly embedded miso soup as an essential food into the popular food culture of Japan. To this day, miso soup is a pivotal component to the Japanese meal and is drank at least once a day by the majority of Japanese. Miso soup is as inseparable to Japanese cuisine as rice, the acknowledged anchor of almost any meal.

right: “ Zen” by Kuniyoshi (1797-1862)

Facts of Japanese Miso

About Fermentation

While most miso is fermented to some degree, there is a wide range of differences between miso in regards to ratio of koji to soybeans as well as fermentation period.

Koji (Aspergilus oryzae) is a spore that has been used for fermentation in Japan for thousands of years. It is the mysterious, magical element that enables complex fermentation of Japanese traditional foods such as miso, soy sauce, rice vinegar, and mirin. Miso with a high percentage of koji tends to be barely fermented, or perhaps better put, matured rather than fermented, and has a quite mild profile. Unfermented miso is more like a salty-sweet condiment—much loved in the areas where it is made and often used for classical preparations in restaurants—this style of miso could be added to cookie or cake batter to give a slight, yet essential boost of richness.

Local areas that make fermented miso crave the mellow and savory characteristics that develop naturally over time. The complex fermentation notes and heady aromas of such miso are highly valued, as well as virtually addicting. and this kind of miso should be considered almost like a savory salt-plus condiment. Also, each miso maker prides itself on making its own proprietary koji since koji is one of the key factors to determine taste in miso. It is said that you cannot make the same miso even when using the same ingredients because koji always develops subtle variations to its flavor profile each time.

Fermented foods introduce probiotics into our diet and are crucial elements to promote good health through cooking. Full flavored and naturally sweet and well-balanced by acid, they add powerful nuances to any dish. Fermenting provides the benefit of preservation while making foods more digestible and more nourishing. Fermented foods are central to artisanal and traditional foodways and defy globalization and industrialization of food in the modern world. And Japan is the country of fermentation.

Worldwide, the fermentation boom has taken hold and miso is the poster child ingredient for this movement: Intrepid chefs and fermentation aficionados are wildly experimenting with the making of any number of unusual misos—some to better degrees of success than other. Nonetheless, the Japanese method of making miso has stood the test of a time without variation over a millennium so this beautifully simple method that follows the natural rhythm of the seasons and the autumn harvest is deserving of the respect it commands. Miso is a homely yet extraordinary condiment that can be the star of a dish or slipped into any preparation as a hidden taste (kakushi aji) to add complexity and beneficial components.

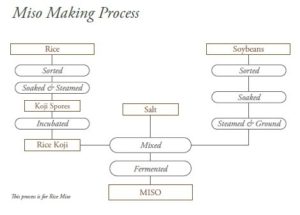

Miso Making Process

Types of Miso

Miso types are determined by the koji-inoculated grain used to make each miso (i.e. rice, barley, or soybean). The process to make miso, whether automated or artisanal, basically does not differ, and involves a two-step fermentation process. The grain used for incubating koji is soaked overnight, drained, steamed 80%, cooled to body temperature and then inoculated with koji spores (Aspergillus oryzae) before being held in a humid anaerobic environment to propogate for 2 days. The koji-inoculated rice, barley, or soybean is mixed with cooked soybeans, which have been soaked over night before steaming and grinding, salt, and sometimes a little “seed miso” (tane miso) from the previous year’s batch. The mash is packed in cedar barrels, enamel tanks, or fiberglass vats, and left to ferment for weeks, months, or years, depending on the type of miso. Good bacteria transforms simple sugars into various organic acids which, in turn, impart distinctive proprietary flavor profiles to the miso while also preventing spoilage.

Kome (rice):

From quick-fermented shiro miso and Kaga miso to 6-months- or 1-year-fermented inaka miso, kome miso represents a fairly wide range of flavors. Quick-fermented varieties are made with an appreciably larger percentage of koji than other misos and have a sweet, only slightly salty profile with little fermentation. These quick-fermented sweeter varieties are good for adding a gentle miso flavoring to vegetable dishes or fish marinades. Inaka miso is an excellent choice as a basic miso since it is mild, yet still has heady fermentation notes for savory dishes.

Mugi (barley):

Soybeans, barley koji, and salt, which are traditionally fermented for 6 months to 1 year (one summer). Soft, luscious, and fragrant from the barley, mugi miso is particularly good in simmered dishes but absolutely delicious in just about anything. Highly favored in Western Europe—perhaps because mugi miso goes well with olive oil.

Mame (soybean):

Long-fermented for 2 to 3 years from soybeans, soybean koji, and salt. Dark and deeply flavored with lovely beery notes, mame miso makes rich winter broths, and is a good candidate for mixing with lighter miso varieties (awase miso) to add overall complexity. Hatcho miso is a type of mame miso produced in Aichi prefecture in central-eastern Japan and is weighted with massive rocks for 2½ years, to promote fermentation and intensity of flavor.

Manufacturing Method: Quality and Safety

From the ultra automated factory to the small artisanal maker, miso production focuses on quality and safety. Japanese soybeans are incomparable since these varieties have been used for a millennium in traditional (non-oil) culinary applications such as miso, soy sauce, and tofu. Large companies focus on making sure no outside pathogens enter the manufacturing process by pasteurizing and heat processing and close quality controls along the way. Whereas small makers maintain a low-tech method but keep a close eye on the fermentation process, thus ensuring a safe well-made product. Essentially miso might develop sourness in the fermentation process, but it does not risk going bad, just under or over fermented. Miso is virtually a foolproof product to create.

How Miso is Made

modern factory with automated work tools at Marukome Miso

Modern factories such as Marukome developed, and eventually flourished, post WWII due to the dire need to feed the Japanese people and to rebuild the food systems, which had suffered from extensive shortages during the war.

The mission statement for Marukome Miso is to create “safe and healthy” miso at an economical cost. Marukome makes 108,000 tons of miso per year and their miso is sold in every locale around the Japanese archipelago and readily

available worldwide. For the most part, Marukome uses a short fermentation time, so the resulting miso is mild in flavor and thus holds wide appeal. Easy to use, Marukome makes multiple types of miso to satisfy a wide variety of palates. And Marukome is affordable for everyone, so really the “miso of the people.”

Large companies are also responsible for introducing new miso-based products

to expand the marketplace. Most notable is Marukome’ s dashi miso, which catapulted Marukome to the head of the pack in 1982, and their more recent liquid-type Miso & Easy product that comes in a handy squeeze bottle. Additionally, large miso producers have played an instrumental role in expanding the accessibility of miso abroad and have effectively transitioned miso into a mainstream staple ingredient found in many kitchens worldwide.

Marukome has become a household word synonymous with “miso,” and this creates a trust with customers, which reaches across generations and country boundaries. Without large miso makers, small makers could not flourish nor promote their products abroad, since small companies have less wherewithal to export. It is safe to say that miso would have remained a niche flavoring, known and used only by the macrobiotic community, had large companies such as Marukome not existed.

Traditional method at Small miso makers

The traditional method for making miso has not altered in over 1000 years. It follows the seasons and the miso is fermented at a natural ambient temperature following the actual outside weather, without temperature controls. This is a quiet production where the miso sleeps and ferments all on its own with minimal interference other than occasional stirring.

Miso companies that follow the traditional method for making miso operate without much machinery and the miso storage houses where the miso fermentsare peaceful places. Making miso in this way, means following the natural rhythm of the seasons. When the weather cools, after the fall soybean and rice harvests, miso can be made up until early spring, when there is about one month left of cool weather. The key point to making miso in the traditional way is to allow the mash at least one month to rest before the warm weather starts to ramp up and the fermentation becomes active.

Small miso makers rely on the best quality soybeans, grains, and salt, and often promote the use of Japanese soybeans, organic soybeans, or better yet, Japanese organic soybeans (4 times as expensive as Chinese or Canadian organic). Also small miso makers following traditional methods often use natural sea salt, as opposed to table salt, since natural sea salt will promote gentle and healthy fermentation. Small miso makers use a low-tech method, which brings out the individual characteristics and flavor profiles in each miso batch. Fermented over time without intervention, the miso is unusually high in probiotics and the other beneficial properties of miso.

Naturally fermented miso adheres to the traditional method followed for hundreds of years in Japan: the season for making miso is in the late fall to early spring with the development of enzymes and yeasts increasing during the fermentation period over the summer as the outside ambient temperature climbs. The Japanese summer is characterized by high humidity and that condition enourages fermentation, thus making Japan the perfect climate for creating seasonings in the time-honored methods where time and natural enzymes do the work, rather than man.

French Cuisine with Miso

Using Japanese Miso

Japanese food has been experiencing a sustained boom in France for several years now and miso as well as soy sauce have become mainstream in French restaurant kitchens. The charm of Miso is most certainly its “umami” as a fermented food. And this “umami” complements and combines well with French cuisine.

To best showcase miso’ s natural “umami,” I first chose a pigeon, a classic French dish. The natural pungency of the pigeon’s internal organs is softened by the mellow salty-sweet miso, creating a synergistic effect. Together with the luscious foie gras and cèpes (Penny Bun mushrooms) a beautiful harmony is achieved on the plate.

Marinating food in miso before cooking introduces “umami” and fragrance to grilled dishes and I encourage world chefs spread the word about using miso as an essential seasoning to not only add “umami” to many foods but also to stretch the horizons of their cooking.

Taichi Nakahiro,

Chef de Cuisine

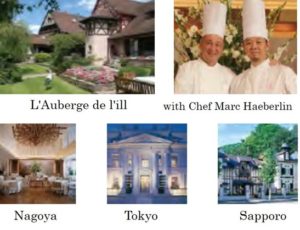

L’Auberge de l’ill Nagoya

Chef Nakahiro has cooked in French restaurants in Japan and France for almost two decades and his cuisine was influenced by a seminal affiliation with France’s prominent Chefs Paul and Marc Haeberlin of L’Auberge de l’ill.

L’Auberge de l’ill Nagoya is an outpost of L’Auberge de l’ill, a 100-year-old French restaurant located in a small village in Alsace, France, which has maintained an impressive three Michelin stars for more than 50 years.

Macarons with Miso

Using Japanese Miso

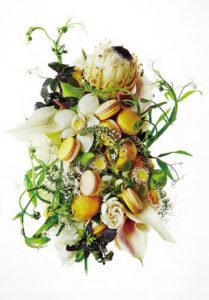

Pierre Hermé is the legendary pastry chef who single-handedly created the world craze for macarons, the crispy meringue sandwich cookies filled with Ganache.

Pierre Hermé is known for the mind-expanding flavor combinations in his signature macarons as well as his elaborately whimsical floral displays created as an interplay to complement these signature macarons.

Pierre Hermé created the groundbreaking Jardin Zen Chocolate and White Miso macaron in November 2015 after returning home to France from a trip to Japan. He claimed you would feel a journey of the senses by this combination, which paired fruity chocolate with the delicately salty white miso.

April 2017 saw the emergence of a new signature macaron: Jardin des Poetes with White Miso and Lemon. And when savoring this unexpected marriage of flavors, you will enjoy sweet, sour, fragrance and bitterness, all in this subtle sweet confection created by Pierre Hermé.

Home Cooking with Miso

For many non-Japanese, miso = miso soup, and this image is deeply imbedded in people’ s perception of miso. But nothing could be further from the truth! Miso is a versatile seasoning that can be used in a wide range of dishes such as dressings, dipping sauces, stir-fries, soups, grilled foods, and pasta.

・A dollop of miso can add an Asian flair and umami to any dish

・As a fermented product, miso marries well with another fermented products such as cheese

・Miso is an excellent gluten-free alternative to soy sauce and can be used in a myriad of ways in gluten-free cookery to bolster flavor

Not just Japanese food, Miso introduces savory notes to many dishes and has a wide range of applications. Think out of the box and experiment!

Tsukiji Cooking is the leading Cooking school for foreign travelers to Japan. The school, in partnership with the Wall Street Journal’s Loyalty Program (WSJ+), offers a variety of premium cooking classes in English by Japanese chefs right in the heart of Tsukiji Market.

Nancy Singlton Hahisu,author of Japan:The Cookbook

Miso may be the most versatile seasoning to have in your kitchen. Think of miso as a richly aromatic, deeply flavorful salt alternative. Used as a hidden taste (kakushi aji) you literally can put miso in anything.

While common logic might prescribe sweet miso for adding to cakes or cookies, I venture to suggest a more powerful miso such as inaka miso, genmai miso, or mugi miso — you only have to use a little to add that back roundness that miso can give a dish.

Cream, butter, mayonnaise, and béchamel sauces love miso. Soups and stews are genius vehicles for adding a dollop of miso — not just dashi-based soups — miso pairs exceptionally well with chicken stock. Also Italians find mugi miso goes particularly well with olive oil, so miso can be introduced to olive oil–based pasta dishes and salad dressings. And miso as a dip for fresh vegetables is a quintessential small bite enjoyed with a cold beer by Japanese farmers in the summer when a salt boost is needed.

Nancy Singleton Hachisu lives on a farm in Japan with her family, and is an award-winning author of three cookbooks: Japanese Farm Food, Preserving the Japanese Way, and Japan: The Cookbook. Her work has appeared in Food & Wine, Saveur, The Art of Eating, and Lucky Peach. A native Californian, she has resided in Japan for thirty years, and is widely respected as an authority on Japanese cooking, both in Japan and the United States, and with chefs around the world.

03-6912-0584

03-6912-0584